High Performance Computational Biology Group

Menu:

Selected Research Projects

Mercury BLAST

Mercury BLAST is an accelerator for the NCBI BLAST tool for similarity search in DNA and protein. NCBI BLAST is used worldwide to compare DNA and protein sequences to databases of known sequence such as GenBank. Matches between a sequence and a database provide clues to the sequence's function and evolutionary history. Among the most important tasks for BLAST are identifying genes in newly sequenced genomes and identifying the genes that give rise to RNA sequences expressed in a sample of cells.

The sizes of today's sequence databases are increasing at an exponential rate, as is the speed at which we can sequence new DNA and thereby generate new input to tools like BLAST. To meet these challenges, we have implemented key portions of the BLAST computation in field-programmable gate array (FPGA) hardware. Our hardware, which resides on a card that can be plugged into a regular desktop or server, is driven by customized software that ties into the public-domain NCBI BLAST codebase. Because we rely on BLAST's own code for many high-level functions, including output printing and assessment of statistical significance, Mercury BLAST presents a familiar face to biological end users.

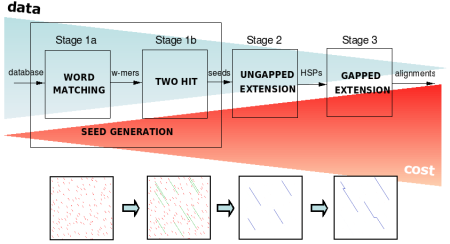

FPGAs have traditionally been used to accelerate dynamic-programming alignment of sequences (the Smith-Waterman algorithm), which is an essential component of BLAST. However, most of BLAST's computation time is spent executing a pipeline of pattern-matching heuristics that avoid the need for dynamic programming. Simply using these heuristics in software makes BLAST on a single processor faster than the fastest hardware-accelerated Smith-Waterman implementations. We therefore devote most of our accelerator resources to the heuristic pipeline, whose components require a variety of implementation techniques to achieve high performance.

The current version of Mercury BLAST runs 10-30x faster than NCBI BLAST on a single AMD Opteron CPU core, while delivering 99+% of the same results. We have accelerator designs for BLASTN (DNA) and BLASTP (protein) and plan to support other BLAST variants as well.

Beginning in fall 2009, we are very interested in identifying biological end-users to receive beta-test versions of our hardware. If you have large-scale BLASTing needs and would like to discuss the potential of our system for your work, please contact PI Dr. Jeremy Buhler at jbuhler AT cse DOT wustl DOT edu.

Principal funding for Mercury BLAST comes from NIH award R42 HG003225. The project is a collaboration between Washington University and BECS Technology, Inc. with assistance from Exegy Corporation.

High-level synthesis of accelerators from recurrence equations

A major impediment in the widespread use of special-purpose accelerators is the work required to design and implement them. We are exploring techniques to automate the synthesis of parallel arrays for dynamic programming algorithms from high level descriptions expressed as recurrence equations.

Many algorithms in domains such as Bioinformatics operate on a large set of discrete, small inputs such as sequences. Traditionally, automated hardware array synthesis techniques have optimized for latency. We have developed a procedure to efficiently find throughput-optimal arrays for any recurrence, which shows significant execution time improvement over latency optimized arrays. A tool implementing this theory helps in automated design space exploration to find high throughput arrays given resource constraints.

Modern computational platforms such as FPGAs support runtime reconfiguration that can select from a small number of arrays optimized for different input characteristics such as input size so as to minimize the overall computation time. An example is shown in the attached figure which selects from five array implementations to speedup the acceleration of RNA folding of pyrosequencing reads by 48% as compared to using a single array. We have developed efficient algorithms to select a limited number of array implementations from a large collection when the input size distribution is known. We have applied these methods to analyze the Nussinov and Zuker RNA folding algorithms which are examples of real world Bioinformatics algorithms which are challenging to accelerate.

Self adapting systems

Most hardware and software systems are built to process many kinds of inputs using the traditional systems' development paradigm that statically accounts for all possible data. That is, all cases are accounted for in advance and the run-time configuration of a system will stay constant throughout a particular run.

Our research into self adapting systems aims to identify correlations between characteristics of input data and possible run-time configurations of the system. Our goal is to identify such patterns and dynamically, and autonomously, allow a system to change its configuration on the fly. One advantage of a dynamically adapting system is to have it run more efficiently. In the specific area of Computational Biology we are working on modeling the algorithms used by Blast and combined with empirical results we aim to find answers to question such as:

- Can we use instantaneous-patterns of the input characteristics to affect, in situ, the long-term performance of the system?

- Is there a correspondence between the performance of Blast's algorithms and the similarity of a subject and query?

- How can run-time parameters be dynamically changed to allow the system to continuously operate at its peak performance on its performance curve?

- Model trends to provide suggested run-time parameters that accelerate Blast performance or yield higher sensitivity.

In the broader sense of performance analysis and queuing theory we are looking for ways to demonstrate how a mathematical model of a system can be used in conjunction with empirical results to teach how a system can be expanded, evolved over time (for example when being ported to a newer computing platform with more resources). If such a theory can be developed it will, for example, be able to suggest design choices that will utilize the new computing platform resources in more effective ways. This will make the design process more of an engineering exercise than an art.